Talk given by Ariel O’Connor, Objects Conservator, Smithsonian American Art Museum. Collaborating and Connecting Ring, Washington Conservation Guild 3-Ring Circus, January 2018, S. Dillon Ripley Center, Smithsonian Institute.

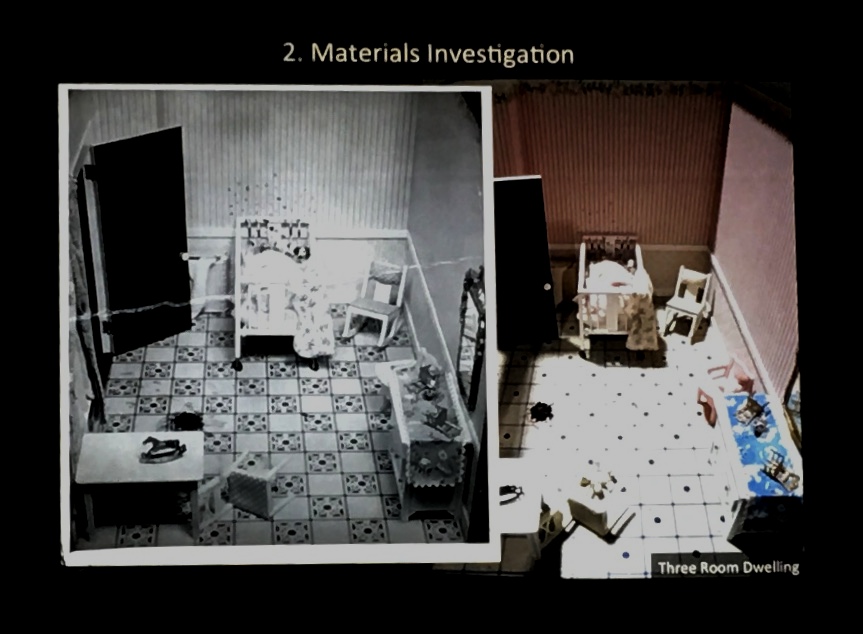

Murder Is Her Hobby: Frances Glessner Lee and The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death, an exhibition held through January at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, explored the intersection between craft and forensic science. The exhibit featured 19 detailed miniature crime scene dioramas, intended and still used for detective training in homicide investigation, and placed heavy emphasis on the material aspects of these creations. The exhibit was dimly lit, creating a mysterious and almost somber environment in which the visitors were given flashlights and become the detectives investigating the crime scenes.

During the 3-Ring Circus, objects conservator Ariel O’Connor gave a presentation highlighting the condition of the materials and the subsequent unintended changes in the interpretation of the clues, as well as the comparability of the fields of art conservation and forensic science.

The first section of her presentation focused on the background and uses of these miniature scenes. The dioramas were created by Frances Glessner Lee (1878-1962), a Captain in the New Hampshire State Police and ‘mother of forensic science.’ The field of forensics was still in its infancy in the early twentieth-century, and there was no formal training for the investigators. Only a few handfuls had medical training that would allow them to determine the cause of death and key evidence was often overlooked or mishandled. To promote a more scientific approach, Lee recreated miniature dioramas of real crime scenes—including even the smallest details down to a cigarette butt—and encouraged her students to look at the materials and clues to solve the crime.

The next section of the presentation outlined past treatments of the dioramas, as well as the conservation campaign in preparation for the exhibition at the Renwick Gallery. O’Connor stated that documentation and stabilization of the multitude of items were two of the most vital steps of the process. She also discussed material issues such as the use of asbestos around light fixtures, which had to be stabilized and consolidated. Another large hurdle was re-adhering loose pieces of evidence. O’Connor mentioned always preserving original materials such as old double-sided tape, since it indicated original placement of objects. She used the smallest amount of new conservation adhesive to the original tape if the material failed.

The age-related changes to the materials used in the miniatures provided an interesting challenge because they had the potential to impact the investigation. Physical changes to the materials had started to alter their interpretation or create false-clues. For instance, the discoloration, cracks, and shrinkage of a cellulose nitrate window caused it to appear as if it had been cracked open by an assailant in an otherwise ‘sealed room.’ The red nail polish used to illustrate blood had begun to fade, discolor, and crack in certain areas, which compromised interpretations drawn from bloodstain patterns and drying time. Treatment compensated for cracking and fading of the ‘blood’ whenever possible. Lastly, O’Connor also discussed the replacement of broken and unsuitable light fixtures with custom-designed LED light units which had the same appearance and color temperature as the original incandescent bulbs. The dioramas were packaged in custom-made boxes and transported from the medical examiner’s office in Baltimore to the Renwick for the exhibition. They will return there on long-term loan from Harvard, as long as they are used for forensic study.

The exhibit, “Murder Is Her Hobby: Frances Glessner Lee And The Nutshell Studies Of Unexplained Death,” ran until January 28, 2018 at the Renwick Gallery on Pennsylvania Avenue at 17th Street NW. Exhibition video, images, as well as an interactive 360 VR of five dioramas are available on SAAM website.

Summary by Hae Min Park, Graduate Intern in paintings conservation at the Walters Art Museum