In case you missed the November meeting, you can watch Tammy Hong’s lecture, Indian Ink? Chinese Ink Sticks (墨) Reinterpreted in Nineteenth-Century Britain, on our YouTube channel: https://youtu.be/U1r1ER0kMw0

As a follow-up to this fascinating talk, Tammy has also answered questions about her research below.

- What role do ink sticks play in Chinese culture? How were they incorporated differently into 19th c. British culture? How does the Roberson box (NGA) reflect these British usages of Chinese ink sticks?

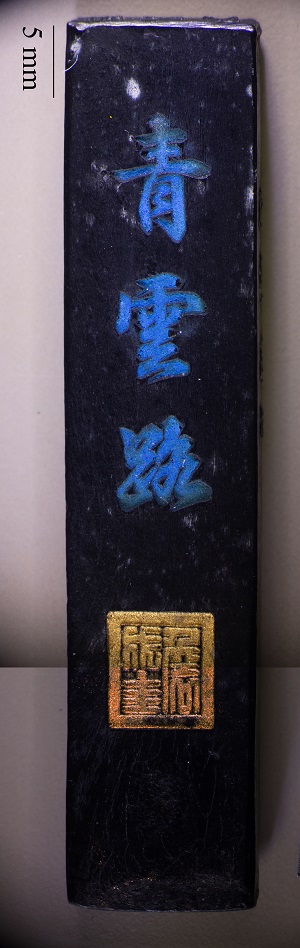

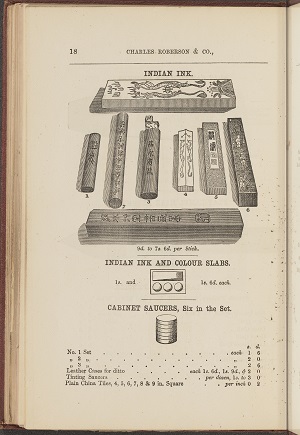

Along with the ink stone (砚), ink brush (毛笔) and paper (纸), the Chinese ink stick (墨) is one of the Four Treasures of Study of Chinese literary culture (文房四宝). Due to the Chinese ink stick’s close ties to the art of calligraphy in China, the ritual of preparing liquid ink from Chinese ink sticks is still implemented to this day. In nineteenth-century Britain, a number of application tools, ranging from hair pencils to quill pens, were used to apply prepared ink (liquid ink prepared from Chinese ink sticks rebranded as Liquid Indian Ink). Due to the Chinese ink stick’s maneuverability as a medium, “Indian Ink” was used in a variety of art practices in Britain ranging from architectural drawings to illuminated manuscripts. Despite the separation between amateur art and professional art in the nineteenth-century British arts education system, the Chinese ink stick was ubiquitous in British art-making practices due to its versatility.

The NGA Roberson box was an award given to an art student for their achievements in their studies, specifically in watercolor. Curiously, instructions for using the Chinese ink stick were excluded from the suggestions for using materials inscribed on the interior of the Roberson box’s lid. This suggests the preparation of the Chinese ink stick was fundamental in an art student’s repertoire and was common knowledge.

How did British Imperialism and the commodification of art play a role in the inconsistent labelling of Chinese ink sticks as Nankin India Ink, Indian Ink, India Ink, etc.?

Documentation and record keeping (in Indian Ink) was pertinent to British empire building in the nineteenth-century. Institutions, governing bodies and companies had meticulous record keeping practices to document formulas of production, to catalog the transactions of commodities and to record the interactions between individuals and communities. Despite so, it is uncertain where the term “Indian Ink” originated from. Interestingly, neither colourmen records nor written documentation that pertain to the larger British colonial historical framework provide accurate accounts of the origin of the term in Britain. In a French source, A General History of China, Chinese ink sticks were already referred to as “Indian Ink.” Written by the French Jesuit Jean-Baptiste du Halde and translated by the English physician Richard Brookes, this influential volume observed that the best Indian Ink – Chinese ink sticks – came from the Chinese city of Nankin. These terms likely influenced the naming conventions of Chinese ink sticks in Britain.

- How did the materiality of Chinese ink sticks play into this reinvention of Chinese ink sticks as Indian Ink? Can you talk about how the concept of ink as solid vs. liquid in Eastern/Western culture might have played a role in this?

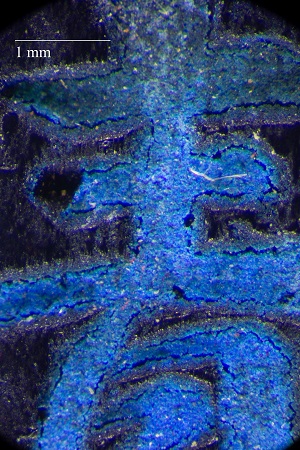

Composed of 90-99% carbon black particles, Chinese ink sticks are carbon black pigments. Carbon black pigments are overall very stable and versatile. Their compatibility with all other pigments make carbon blacks highly desirable in an artist’s practice. The minute carbon black particles in Chinese ink sticks were thoroughly combined with animal glue binder in a rigorous pounding process (Chinese sources suggest that the clay mixture must be pounded 30,000 times!). The pounding process accommodates the hydrophobic characteristics of carbon black particles by forcing as much animal glue as possible onto the hydrophobic surfaces of these particles to facilitate the medium’s even dispersion and adhesion to surfaces. The ink-making process is likely what makes the Chinese ink stick superior to other carbon black pigments like lampblack, ivory black, bone black and vine black that commonly use plant based gum-Arabic as their binders.

The term “ink” corresponds to two distinct concepts of ink in China and Europe. The term for ink in Mandarin, “墨 (mò),” refers to the solid ink stick, whereas, in the European context, “ink” refers to an aqueous solution. To fully address the histories associated with ink in both its solid and liquid forms, “墨水 (mò shuǐ),” and “墨汁 (mò zhī),” Mandarin terms that describe prepared ink, must be taken into account whenever researching these ink traditions and writing about them.

What surprised you while working on this project?

So many things! This whole project began with a surprise. I came across a 19th-century Charles Roberson & Co. catalogue while I was matching some of the vintage artists’ materials in the Art Materials Research and Study Center to their manufacturing history. I immediately noticed that one of the Chinese ink sticks on the page was printed upside down (the Mandarin characters on the stick was upside down). I then noticed that the ink sticks were labeled as “Indian Ink.” I was very baffled because I always knew “Indian Ink” as an aqueous drawing medium while Chinese ink sticks were what I grew up using in Chinese painting and calligraphy. How were these mediums connected? The art detective in me had to find out.

- Why do you think this history is understudied in the West?

There has been a lot of interest in Chinese ink sticks in the West since the 1800s, but scholarship that deals with the intersection between Chinese and European ink traditions is lacking. I think the system in which we examine history that focus on geographical regions and movements do not encourage us to explore cross-cultural narratives when looking at artifacts. Perhaps the lack of interest on the topic and the lack of interest in overcoming the language barrier are outcomes of this framework.

Where are you going with this research in the future? What questions do you still want to know the answers to?

My immediate next step for this project is to examine the Chinese ink stick samples that I prepared pre-COVID with PLM in hope of further understanding the materiality of this medium and its relationship to the other components in the Roberson box.

The binder material and additives in Chinese ink sticks are some of the topics that I want to investigate further. In my research on carbon black pigments so far, it is clear that the additives, whether it be shellac or different plant and animal glue binders, were what defined the functions and behaviors of carbon black pigments when applied. Three types of raw materials were cited to be the source of animal glue in Chinese ink sticks: skins of large animals, deer antler and fish skins. I’m curious how these materials were sourced, chosen and incorporated in the ink-making process (I believe out of the three sources, fish glue is the only adhesive that is liquid at room temperature, while the other sources are solid).