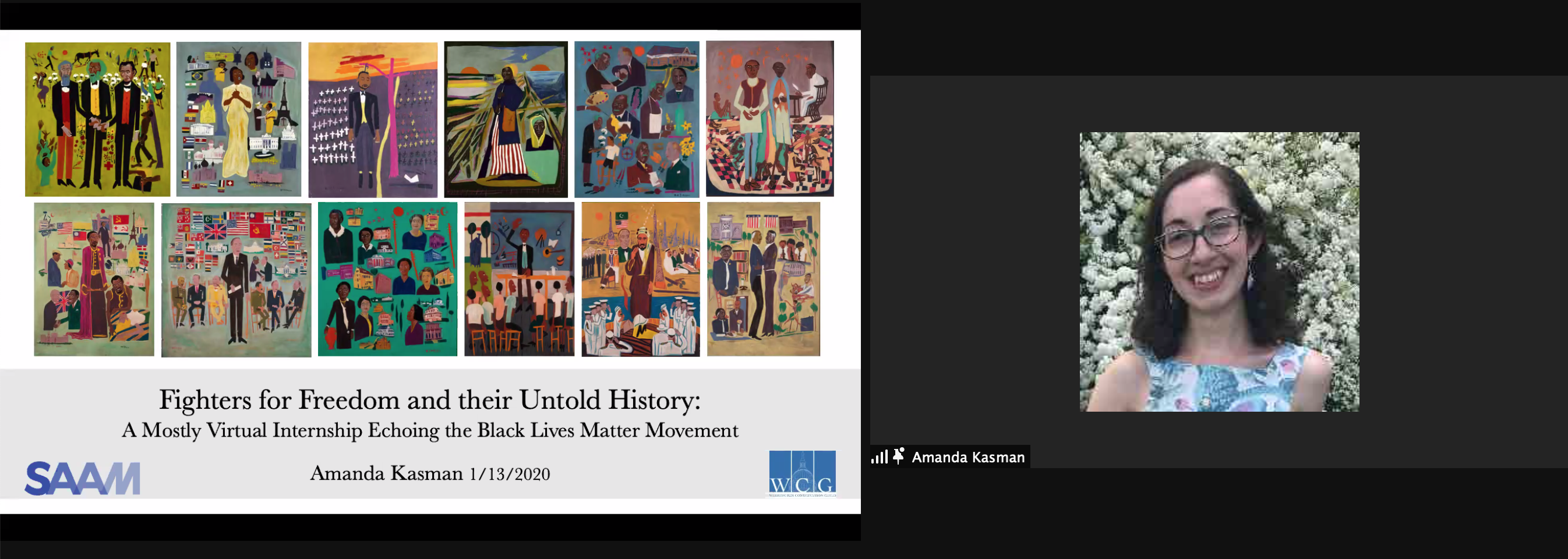

The second talk of the evening was from Amanda Kasman, third-year Graduate Fellow at the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation. Kasman’s talk, titled “Fighters for Freedom and their Untold History: A Mostly Virtual Internship Echoing the Black Lives Matter Movement,” was a reflection on her Summer 2020 graduate internship at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM). What was planned to be a treatment-focused internship turned into an almost entirely virtual internship due to the global pandemic. This shifted the internship’s focus to research the history and practice of artist William H. Johnson in preparation for a traveling exhibition planned for 2022.

William H. Johnson (1901-1970), an African American from South Carolina, was a prolific painter. While his early style was realistic, he ventured into Expressionism during his education in New York. Then after spending a decade in Europe, where he found social acceptance, more opportunity, and met his wife, Johnson settled on a folk style primarily depicting Black culture. The subjects of his paintings ranged from religious scenes, to rural life, to family members, and recognizable historical figures. In his time, Johnson was criticized for his “uneducated” style, despite having a formal art education. A combination of a lack of commercial success, financial instability, personal tragedy, and illness, joined with institutional racism led to him to be institutionalized in an American mental hospital in 1948 where he remained until his death in 1970. At the time of his arrest, Johnson had 1,200 works on his person; which were confiscated and deemed worthless by an appraiser before being gifted to the Harmon Foundation.

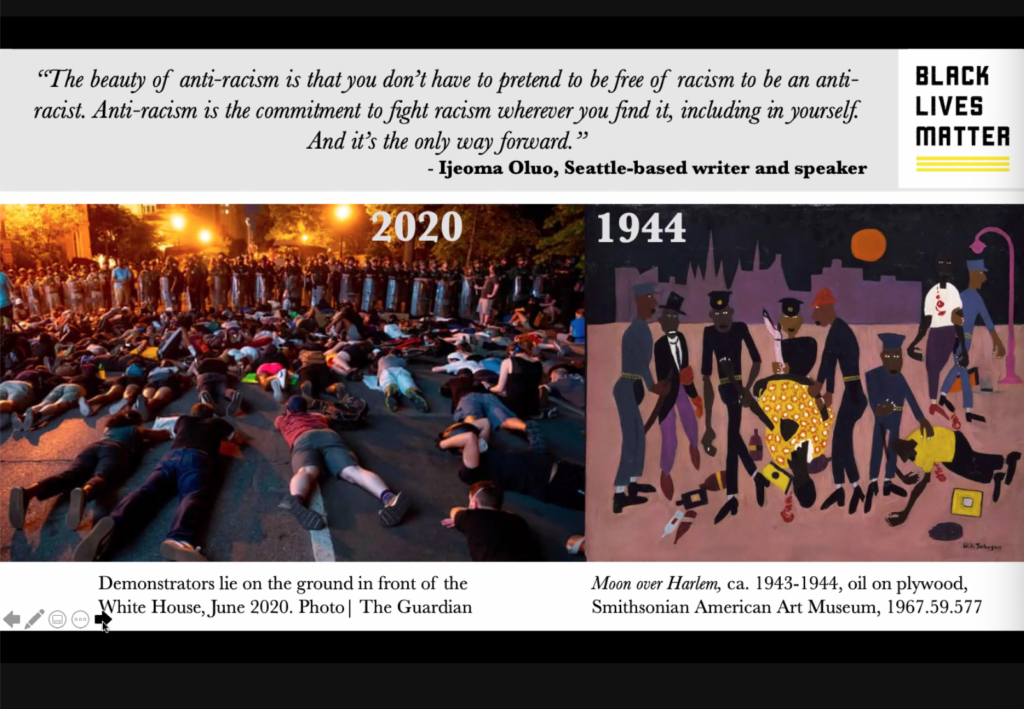

Kasman’s research of Johnson’s life and art paralleled many of the themes of racial injustice brought to the forefront by the Black Lives Matter Movement in the summer of 2020. These tragic and heroic tales left Kasman wanting more information omitted from history textbooks. In her talk, Kasman asks the question, “What else was I not taught?” and addresses the zoom audience with a pop quiz, sharing the following:

- The first casualty of the Revolutionary War was Crispus Attucks, aka Michael Johnson (1723-1770), an African-American and Indigenous former enslaved person;

- Harriet Tubman, aka Araminta Ross (1822-1913), developed narcolepsy after an injury inflicted by her master, and after the Underground Railroad, became a spy for the Union Army;

- Dr. George Washington Carver (1864-1943) didn’t just love peanuts; he revolutionized the practice of farming by introducing crop rotation to sharecroppers

- and, Josephine Baker (1906-1975) received the Medal of Honor for her work with the French Resistance during World War II propelling her to become a global advocate for desegregation.

Kasman considers whether the absence of these facts from her education evidence a “deliberate repression of history” and is actively seeking to fill in these holes in her knowledge of American History left by mainstream education.

During the question-and-answer portion, attendees were curious about Johnson’s artist materials, presence in Europe, and if this presentation for the WCG meeting will be presented to a broader audience in the future. Since Kasman was not on site for the majority of the internship, most of the examinations of Johnson’s works were completed online. It seems as though he was an economical painter, and a lot of his works are oil on board. Kasman and Keara Teeter, current Samuel H. Kress Fellow in paintings conservation at SAAM, will present on the conservation treatment of Johnson’s paintings at AIC’s annual meeting in the summer of 2021. When asked by an audience member how these “rediscovered histories” personally affect conservators, Kasman humbly stated that researching the stories behind the paintings paired with open communication with stakeholders is imperative for conservation.

For more information on William H. Johnson, please follow the links below:

- Fighter for Freedom Traveling Exhibition 2022: https://artbridgesfoundation.org/exhibitions/marketplace/william-h-johnson-fighters-for-freedom

- SAAM Eye Level Blog: https://americanart.si.edu/blog/preserving-william-h-johnsons-fighters-freedom-series