3-Ring Circus virtual meeting summary (January 6, 2022)

Ring 1: Conservation in Practice

Conservation and Preservation Strategies for Royal Painted Tombs in El-Kurru, Sudan: Acknowledging the Past while Planning for the Future

Presented by Janelle Batkin-Hall, Objects Conservator

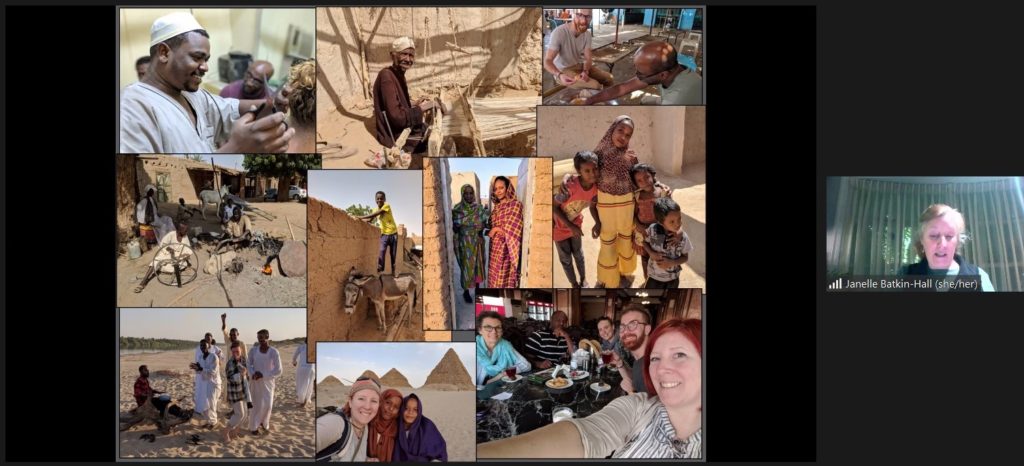

Ring 1 of the Washington Conservation Guild’s annual 3-Ring Circus took place on Thursday, January 6, 2022. Although hopes for an in-person meeting were high, the Guild opted for a virtual venue after considering the rise in Omicron coronavirus cases. For the final lecture of the night, Janelle Batkin-Hall shared her experience treating the rock-cut painted tombs of King Tanwetamani and his mother Queen Qalhata in El-Kurru, Sudan. The talk opened with an introduction to Batkin-Hall who—in addition to being an objects conservator in private practice with a degree in archaeological conservation specializing in cultural heritage materials from Buffalo State College—is a collector of Victorian human hair art and an artist who incorporates such weaving techniques into her own work. Previously a Mellon Foundation Fellow at the National Museum of African Art, she is currently under contract at the National Air and Space Museum.

Batkin-Hall began with an acknowledgment of the Piscataway tribe: elders, the community, and past and future generations. Because the lecture was based on a paper she co-authored, she then acknowledged her colleagues Pamela Hatchfield, Jan Cutajar, Eve Mayberger, and Camille Bourse. The paper itself can be read on Research Gate (link below). Batkin-Hall explained that the UNESCO World Heritage Site of El-Kurru includes a burial site for Kushite conquerors of Egypt, who ruled as its twenty-fifth dynasty, as well as a large Sudanese pyramid of an unknown king and a mortuary temple. The tombs of Tanwetamani and Qalhata are among the best-preserved Kushite tombs. Here she threw in some fun facts: Sudanese pyramids pre-date Egyptian pyramids and exist in greater numbers, around two thousand Kushite to two hundred Egyptian. For further contextualization, she gave an overview of preservation efforts at the site, which began in 1919 with an excavation by George Reisner, one of the first archaeologists to utilize scientific documentation and photography in fieldwork. The International Kurru Archaeological Project (IKAP) was formed in 2013 by Dr. Geoff Emberling (Univ. of Michigan) and Dr. Rachael Dann (Univ. of Copenhagen) to address stabilization and long-term preservation of the El Kurru site. In 2019, a team of conservators from the Boston Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) returned to site to assess accessibility, perform stabilization, and develop a plan for long-term preservation.

Unlike Egyptian pyramids, explained Batkin-Hall, the Kushite burial chambers are not located within the pyramid, but are subterranean, cut into the sandstone deep in the ground. The subjects of the talk, the tombs of Tanwetamani and Qalhata, lack their original pyramid superstructures, but are themselves much intact. Antechambers lead into the funerary chambers, which feature elaborate paintings on the walls and ceilings. The sandstone bedrock walls are covered in plaster, a white pigment ground, and earth-pigment decorations. Qalhata’s decorations show her holding the hands of the children of Horus. She is presented in the funerary chamber holding the ankh (“key of life”) and undergoes phases of rebirth. Batkin-Hall noted that much of the loss of the painted surface occurred in the lower register of both tombs. The MFA condition assessment for these tombs took place in 2018. It was determined that this loss in the lower register and abrasion to a cartouche took place in the past century, using photos from the Reisner excavation as reference. Certain environmental factors contributed to degradation, such as the fragility of the sandstone and moisture in the chambers. Insect activity also weakened the integrity of the surface. MFA conservators used annotations on printed photographs (later digitized), written documentation, photography, and pigment analysis in their condition assessment. Further testing of materials was performed at the MFA as they developed a treatment plan. Here Batkin-Hall emphasized the importance of collaborative decision-making between the conservation team, Sudanese officials, architects, engineers, and the local people in Kurru. Also in 2018, an environmental monitoring plan was implemented on site. Interestingly, a link was found between the wall damage and the floors. The uneven ground caused visitors to regularly use the walls to steady themselves. Landscaping fabric was placed in the chambers and weighted down with stones from the Nile to address this issue. Railings and steps were installed to improve accessibility between tombs and mitigate risk to the walls.

Moving onto materials and treatment, Batkin-Hall discussed the main concerns of the team. They selected materials based on durability, reliability, and ease of application, while making conscious effort to source locally (Sudan). As an aside, Batkin-Hall addressed some of the challenges they experienced while sourcing materials and setting up the work site. Unable to locate natural hydraulic lime in Sudan, they imported Void-span mortar systems from the US, which were selected in part for workability and minimal use of moisture. Lack of electricity also presented a problem. She described long chains of extension cords stretched across the desert to the local village. Local electricians helped maintain the electrical supply and battery powered Dracast LED lights were set up on site to minimize heat generation. To ventilate the underground tombs during the solvent stage of the treatment, an Allegro exhaust fan and Grainger ducting system was set up. Although the system was noisy, Batkin-Hall noted it was useful and could be broken down to fit into a single checked bag for transport.

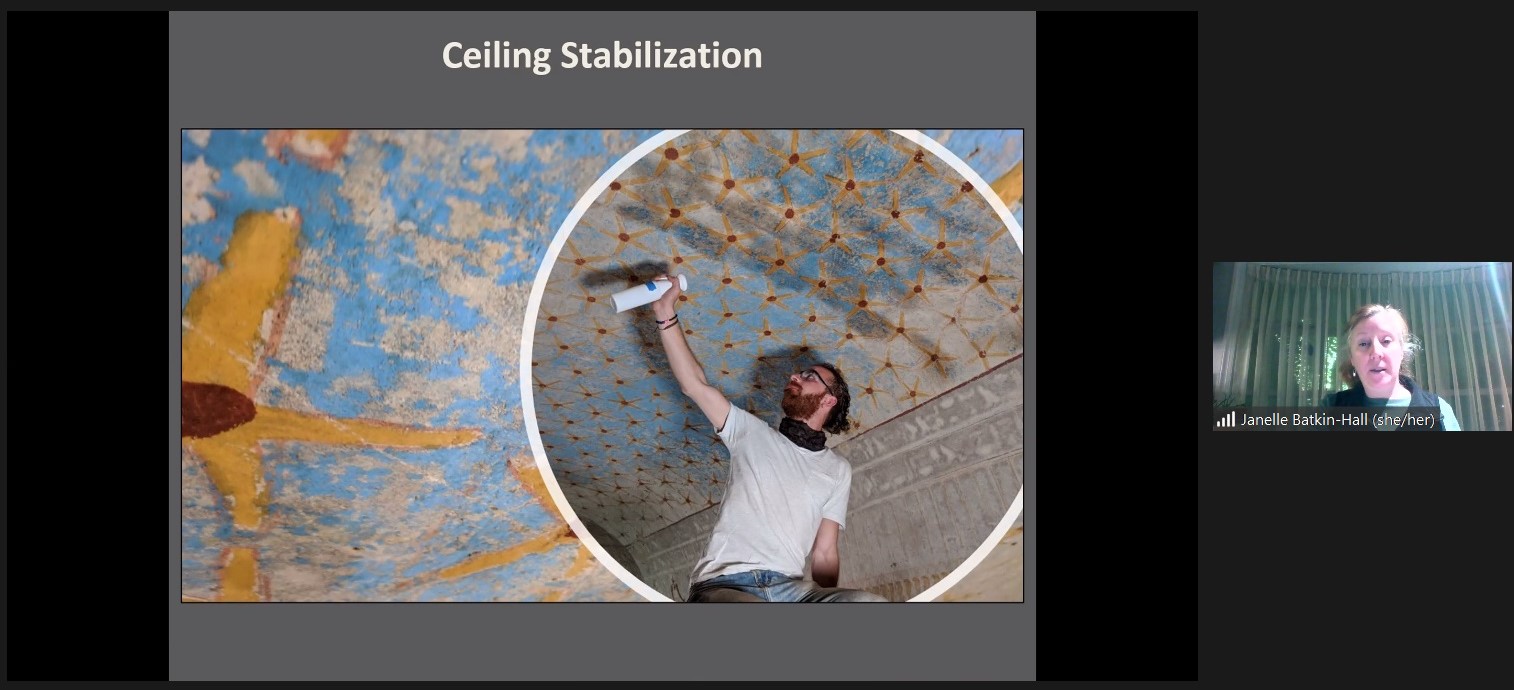

Because Qalhata’s tomb was in poor condition, treatment in 2019 focused on the stabilization of the walls, consolidation of the ceiling paint, removal of insect debris, and limited removal of silt residue. Batkin-Hall and her colleagues filled voids by injection-grouting, performed edge repair on friable plaster, and used nebulizers to apply consolidant to the friable ceiling pigments. Using Butvar B-98 (a polyvinyl butyral resin) in ethanol, they consolidated the sandstone before attempting mortar injection. Mortar was mixed 5:1 filler to water and color-matched with dry pigment. Edges of insect channels and exposed substrate were filled with Void-span Crack Filler.

The Egyptian blue of the ceiling presented more of a challenge than initially expected. Tri-Funori, which had shown promise in 2018 tests, proved impractical on site when the necessary concentration clogged their sprayers. After further testing, they switched to a 7.5% solution of gum Arabic in water, applied in two coats by nebulizing sprayers. To address distracting evidence of insect activity such as egg sacs and spider webs, they softened such debris with ethanol or water-soaked swabs and removed it mechanically. Finally, the team addressed silt residue on the lower register of the tomb paintings. Red pigment obscured by the silt residue required a different approach than other pigments in the tomb successfully consolidated with the gum Arabic or Butvar B-98. To comply with Sudan’s National Council for Museums and Antiquities (NCAM) request for improved legibility, they localized treatment, targeting silt on the white background of the paintings for removal, while leaving the residue on the red pigments, thereby creating visual contrast and improving readability.

Batkin-Hall closed her talk by acknowledging the importance of preventive conservation in long-term preservation efforts. The team at El Kurru drew up several recommendations, ranging from limiting access to the more sensitive areas of the tombs to simple signage regarding visitor conduct. During the Q&A session with the audience, Batkin-Hall addressed the sourcing of nebulizing sprayers, which had been provided by her Danish colleagues, and concerns over flooding and future insect damage. Although not much can be done to prevent future flooding, she told the audience that the last known flooding occurred prior to the 1919 excavation. Regarding insect activity, the damage appeared to be older, but on-site guides perform active monitoring.

Summary by Sam Callanta, Mellon Opportunity for Diversity in Conservation Cohort 2020/21

Meeting attendance: 84 participants

Links

Research Paper:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342659902_Working_Together_Community_Conservation_and_Preservation_Strategies_for_Royal_Painted_Tombs_at_El-Kurru_Sudan

Products:

https://www.talasonline.com/Butvar-Resin

https://tri-funori.com/adhesive/

https://www.voidspan.com/phl-products/

Institutions/Organizations:

https://ikap.us/

https://www.mfa.org/