Naval Lodge No. 4

Saturday, November 16, 2024

Morning Session

Summarized by Alice Craigie, Modern Painting Fellow National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

For information about the afternoon session, please see the summary of the second half of the event, by Charlotte Starnes.

The WCG Private Practice Seminar, held on Saturday, November 16th, 2024, was the first gathering focused on this topic since 2000. This seminar aimed to provide comprehensive knowledge on the business aspects of private practice crucial for conservation professionals. The morning session was attended by 39 people and featured four in-depth 30-minute presentations that covered various topics, including contracting essentials, legal entity setup, business insurance, and taxation. The speakers shared a strong emphasis on the importance of clearly defined contracts, and the presentations offered practical insights into establishing and managing a successful private practice.

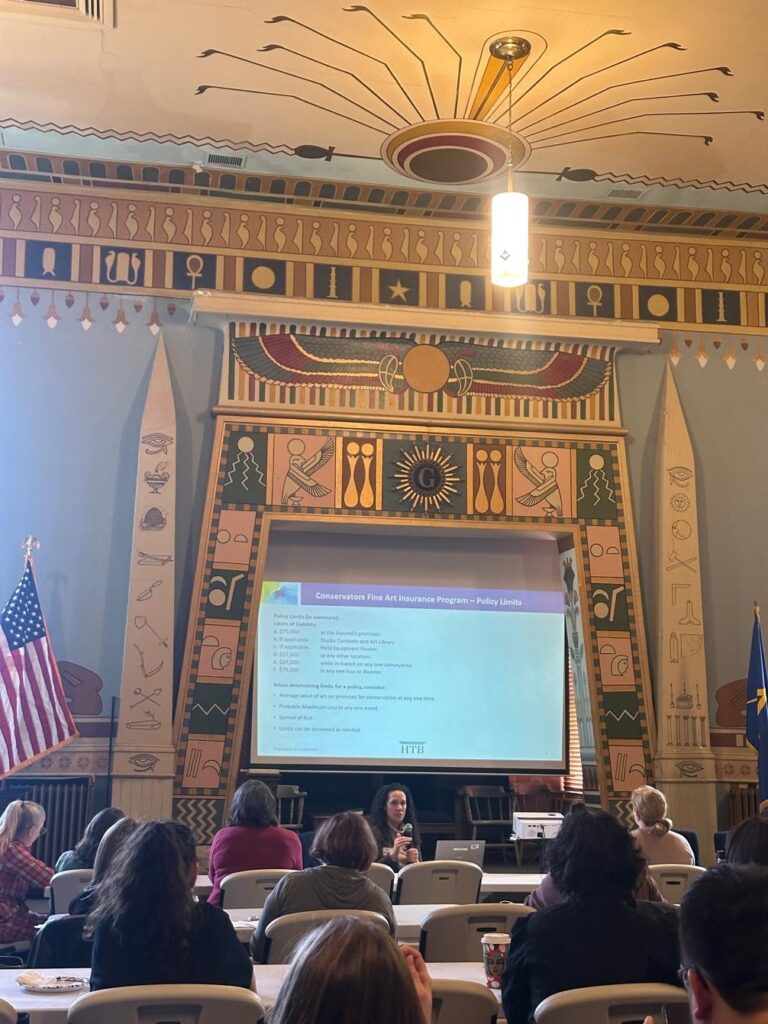

The seminar opened with Casey Wigglesworth, Vice President of Fine Art Insurance with Huntington T Block, who presented insights into fine art insurance for conservators. Several members of the audience have acquired insurance through T Block and they have a longstanding history of working with conservators. Casey’s presentation broke down insurance essentials alongside various types of insurance T Block offers. Casey stressed the need to assign a value to the object treated and how that is essential should any loss ensue. The Fine Art Insurance policy offers coverage starting at $75,000, with careful consideration given to the potential maximum value of artwork. The policy covers physical risks like fire, flood, theft, and accidents but excludes wear and tear and inherent conservation issues.

When determining insurance, conservators should focus on the highest potential value of artwork and require clients to specify a value that is written into contracts. Never suggest a value yourself. Casey emphasized the importance of documenting the artwork’s condition, especially when concerned with transit and handling, as these are the most risk-prone periods. Furthermore, the transit coverage is deliberately set lower to discourage conservators from transporting art themselves.

While having security is technically a recommendation rather than a requirement for insurance, it was discussed how security is crucial, with suggestions for central security systems and careful risk management. Casey noted that if you had a system like Ring for central security you would need to have a membership option that contacted a third party – not your cell! The insurer will consider the ‘spread of risk’ and probable maximum loss, i.e. where objects are placed in relation to each other and proximity to windows and exits or how long might It take for a flood to encompass the space. Casey suggested spreading valuable items across a workspace, perhaps keeping a designated section of the studio solely for completed projects. It was also noted that while investing in security may be expensive, you can sometimes claim homeowners credit, which could offset the cost.

Valuation is based on replacement cost at the time of purchase, not current market value if bought now or its sentimental worth. It was recommended to maintain detailed inventories of items and their current value. Insurance adjusters will investigate losses, requiring proof for high-value items. The policy is worldwide but requires a US address and includes an application process that involves submitting a professional resume and loss history.

Casey discussed how you can set insurance at the lowest limit and increase per project then off-set the additional cost to the client. She stressed that one should replace terms like “insurance premium,” with “administrative” or “operational” fee as you are not an insurance broker. The insurance focuses on protecting against sudden, unexpected losses that could cause financial hardship, not inherent vice or things related to conservation. If clients wish to cover their own work, you need to have a certificate of insurance and a ‘waiver of segregation’ – this means the insurance company can’t seek you out as the negligent party to recover the cost.

Finally, Casey assured attendees that if they did suffer a big loss, it wouldn’t be hugely detrimental to their future insurance costs. However, if you claim recurring loss over a longer period, then that could affect you. This was called frequency over severity, i.e., if you repeatedly claimed for theft, the company may question whether you have put measures in place to minimize this risk reoccurring.

The second speaker was Lauren Horelick, Conservator at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, who shared her expertise in navigating conservation contracts. She aimed to help professionals understand the complex language associated with federal contracts that once intimidated her.

Key Contract Terminology

- ‘A bid’ is essentially a job application.

- SOW (Statement of Work) is the job description.

- RFQ (Request for Quote) are bidding instructions for potential contractors

- SAM (System for Award Management) is crucial for federal contracting. To work on federal contracts, conservators must register in the System for Award Management (SAM), a process that takes about two hours to complete and requires 10 days for approval. Lauren recommended using an email you don’t often use as they spam! SAM is always free and you will never have to pay to register or update-be aware of scammers.

- NAICS code 541990 helps register as a “other professional/ scientific series” This will help COTR’s find you in SAM and reach out requesting quotes.

- The Contracting Official Technical Representative (COTR) manages the contract processes. They are not necessarily a conservator but must undergo an in-depth training on all of the legalities and rules for handling federal funds.

Contract selection is based on either (A) lowest price or (B) best value, with experience playing a crucial role in determining the most suitable candidate. It is up to the COTR, not the contracting office, to establish what rates are considered reasonable. An example of ‘best value’ would be if everyone’s bids came in at the same rate, the person with the most experience may then be selected. Applications are reviewed anonymously and by a committee that the COTR must assemble along with the list of criteria for evaluation to ensure fairness and transparency.

Bidders must carefully address all mandatory requirements directly in their proposal as described in the criteria. Contractors and COTR’s need to be aware of potential personal liability and must maintain no conflict of interest. Unnecessary additional information can detract from the core application and should be avoided.

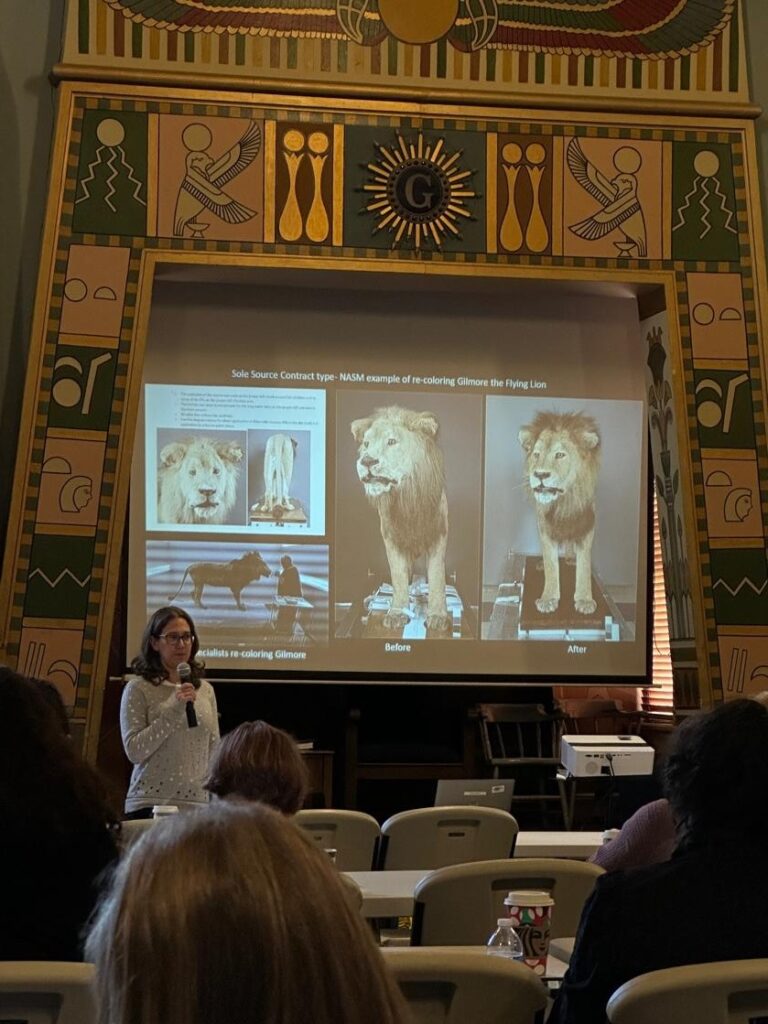

Some contracts may be written for a specific contractor and these are called ‘sole source contracts’ written for specific specialists with particular skills. The government tries to avoid sole source contracts because they are not competitive and consequently sometimes include specific requirements. Lauren shared a project example where a sole source contract was written for a conservator who had specific skills and his contract included using a time-lapse camera for documentation.

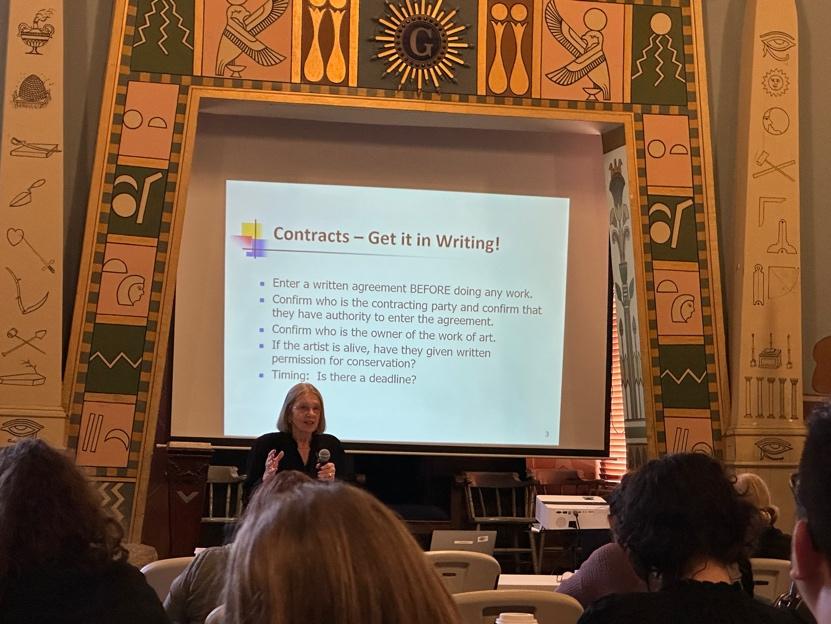

The third presentation was delivered by Janet Fries, Senior Counsel with Lutzker & Lutzker LLP. Fries holds a Master’s degree in fine art photography and specializes in copyright advice and contract negotiation for art-related clients including artists, collectors, authors and filmmakers. She emphasized the critical importance of having clear written contracts for conservation work. Fries broke down her talk into two key areas; Contracts and Moral Rights.

Regardless of whether the client is institutional or an individual, contracts must specify who has the authority to hire the conservator and confirm that all parties understand the terms of the work. The Copyright Act was amended by the Visual Artists Rights Act (VARA) to provide living artists with certain rights, i.e., the rights of attribution and integrity, though these rights only apply to works that exist in a single copy such as an original painting, drawing or sculpture, and to prints and photographs that are signed and numbered, were created for exhibition and are part of an edition of 200 or less. The right of integrity prohibits the distortion, mutilation or modification of a work of art, so conservators should be especially careful with the works of living artists. Written consent should be obtained from the artist before doing any conservation work, even if the artwork is owned by a gallery or museum. Janet noted that if the owner wants conservation treatment but the artist does not, you cannot undertake the work. The caveat to this is if the artwork was made prior to 1991, when VARA became effective. An artist’s consent should be more than a casual conversation, it needs to be in writing. An attendee asked If there was a threshold of due diligence for reaching out to artists who may be unresponsive – Janet advised that there are no specific rules, but it is important to keep records, i.e., who you contacted and how many times you called, wrote and/or emailed. Furthermore, if you work on an object where the artist is unknown, but you suspect they could still be living, try putting the emphasis on the client, they should have provenance records!

Contracts should clearly outline who will perform the work, with no assumption that assistants can take over without prior agreement. Detailed documentation of the artwork’s condition before (and after) any conservation work is essential. Timing (such as treatment duration or deadline expectations), and specific responsibilities must be explicitly stated in the contract. Art packing and transportation costs should be clearly assigned to avoid potential disputes.

In case of disagreements, mediation is recommended over arbitration, which can be extremely costly. Mediation can often be more flexible, sometimes clients just want a formal apology or a trade. Arbitration can be extremely costly as arbitrators tend to be retired judges and Janet had not recently seen an hourly rate of less than $1,000! Fine art insurance with minimal exclusions can provide additional protection for conservators. Conservators should develop a standard agreement template and maintain detailed records of all communication, especially when attempting to contact artists. Moral rights apply only to living artists and the “dead hand rule” means artists’ permissions are not required for conservation on the works of deceased artists.

Setting a liability cap in the contract, while potentially unpopular with clients, can provide important protection for the conservator. The contract should provide a clear but non-detailed explanation of proposed conservation techniques.

The final speaker for the morning session was Tia Cantrell, owner of North Bethesda, and a Certified Public Accountant (CPA), who explained the critical differences between business structures and setting up your practice as a Sole Proprietorship or Limited Liability Company (LLC). In a sole proprietorship, business owners can be personally sued, whereas an LLC provides a protective legal barrier where only company assets are at risk.

The Corporate Transparency Act introduces new reporting requirements for businesses, and S-Corporations have specific filing deadlines (3.15.24) and tax advantages. An S-Corporation offers the benefit of avoiding self-employment tax, which can be financially advantageous for small business owners.

For professionals working part-time or in private practice, forming an LLC is recommended to protect both personal assets and business interests. Maintaining a completely separate business bank account is crucial for financial clarity and potential future audits.

Business expense deductions require careful consideration, with expenses needing to be “ordinary” and necessary for the specific profession. Professional development, conferences, and specialized work equipment can typically be claimed as business expenses, while entertainment costs are not deductible.

Professionals are advised to consult with an accountant to understand the specific tax implications and requirements for their unique business situation. Documenting and tracking all potential business expenses is essential for accurate tax reporting and maximizing potential deductions.

Overall, participants gained a detailed understanding of legal and financial considerations for working as an independent conservator. The seminar provided logistical insights into business structures, insurance requirements, and effective contract development and management. The speakers shared valuable expertise aimed at helping conservators navigate the complex landscape of private practice. While lots of technical information was shared, each presenter kindly agreed to share their PowerPoint for future reference!

2024/2025 WCG season memberships are $35 for professionals, $25 for renewing emerging professionals, and free to emerging professionals who are entering their first season as a WCG member.

Join or renew at www.washingtonconservationguild.org/membership.