With over 100 attendees, Nicole Peters and Ellen Carrlee began their virtual presentations for WCG from Piscataway and Tlingit lands, respectively. Nicole Peters started out with a presentation on her experiences working in private practice throughout the state of Alaska. Peters fell in love with Alaska during an internship with the National Park Service in 2012, and following her graduation from the Buffalo State College program in conservation, she moved there. Working in a “backcountry conservation” style, Peters found contracts across the state and started each treatment with open dialogue about the history and use of the objects. Her traditional conservation training was challenged with the unique needs of the communities; typical conservation repairs would simply not do for belongings that are still fulfilling an active purpose. As Peters approaches an object treatment, she acknowledges her role with the object and people, supplying the stakeholders with transparent information and levels of intervention to choose from. Whenever possible, she likes to involve the connected individuals in her repairs. Their personal knowledge of the object, its use and significance, can then be considered when designing a treatment plan, and in this way she is caring for the object and the people, present and future.

Peters is excited to collaborate with individuals and museums alike, and is working with the University of Alaska Museum of the North on the Indigenous Watercraft Project. Using the SAR Guidelines for Collaboration, this project seeks to meet the needs and goals of Alaska Native peoples while also fulfilling the mission of the museum to preserve the history of the state. She comes to each meeting with reverence for the people and objects and emphasized that no matter the size of the project or client, clear communication is important to begin collaboration.

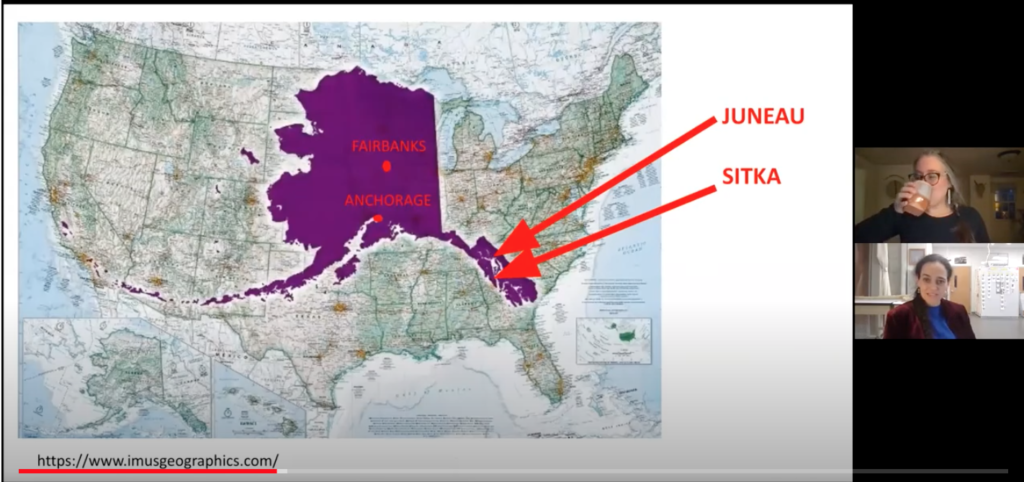

Ellen Carrlee has been the Objects Conservator at the Alaska State Museum in Juneau since 2006. She moved to Alaska after her graduating from New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts and recently earned a PhD in Anthropology from University of Alaska, Fairbanks. Carrlee started her talk illustrating the sheer size of the state of Alaska, noting that if it was cut in half, it would still be the first and second largest states, while holding a population similar to that of the District of Columbia. As a conservator for the State Museum, she is part of a small staff who care for over 40,000 objects. There were three lessons that being a conservator in Alaska has taught her that she wanted to highlight:

(1) Objects are important because objects are important to people. Recently Carrlee has been working with a group of weavers to explore the technologies and values used in dyeing and weaving Chilkat robes, a ceremonial garment. Collaborating with Native weavers, the Alaska State Museum, and scientists at Portland State University, analysis and experiments are being explored in tandem to understand more about the historic practices of Native makers. This work is being done to inform and benefit the Native weavers. Carrlee also brought in a Tlingit weaver to repair a Chilkat robe in the museum’s collection; a practice that is meaningful for the weaver and the garment alike.

(2) Networks of relationships are important; we are not alone in our authority to care for material culture and we are not alone in our treatment strategies and dilemmas. Working with other conservators, hosting interns, connecting with other institutions, and engaging cultural experts as part of a museum team has created a web of people, linking resources and findings. An example of how powerful these networks can be, Carrlee admired the Smithsonian Arctic Studies Center’s “Material Traditions” series for its model of connection (see links to videos below).

(3) Time and resources are limited. Carrlee advised colleagues to pick a passion project. Collaboration takes time from everyone in these built networks, and focusing a specific material helps build deeper connections with Native experts and makers.

Audience questions poured in, asking about techniques and looking for advice on how to start these collaborative practices outside of Alaska. When asked about what the conservators have learned, materially, from these interactions, both Peters and Carrlee spoke instead about creating opportunities for Indigenous people to work directly with objects of their culture. Creating a scenario in which there is an exchange of knowledge and benefit are very important. Peters shared experiences of giving space and time for culture bearers to be in the room during the treatment of these belongings. The individuals could share their knowledge of the object’s past and current use, explain the significance, and tell stories. For example, while working on a drum, Peters was told that the wear patterns were from the specific way this drum is played in a ceremony. Additionally, using more traditional materials for repair – outside of the typical conservation toolkit – has been possible through this collaboration. In regards to resources, as Alaska is remote and getting to sites and shipping materials is expensive, Peters noted that there is a lot of logistical planning to consider. When working with pesticide residue concerns, education on handling protocols is important as analysis is not always available. When possible, Peters will leave extra materials (gloves, etc) with the group. Carrlee spoke about her experiences creating opportunities that will directly benefit the source communities. For example, what materials or knowledge from our field can we give to Native artists? Carrlee also has created internships and contracts for this work, for example working with Tlingit weaver Anna Brown Ehlers to repair a Chilkat robe. In these instances, giving space and time to what the culture bearer may need is important, and it may be completely out of the conservation lab “normal.” Carrlee noted the presence of raw materials and personal regalia during repairs. She also remarked that having food available, a sense of true hospitality, has helped establish a sense of community and collaboration.

Asked for advice on how to establish these connections, both Peters and Carrlee talked about being clear, honest, and upfront. This is also important for when stakeholders are at odds: giving options with clear explanations can help with decision making. Creating relationships and trust are important; these are not and should never be transactional or short term relationships. Carrlee first connects with artists who regularly use the materials she’s interested in because there’s an automatic common ground in working with objects hands-on. Approaching the objects and their materials with respect for their personhood is a “non-verbal, non-academic equalizer.” Peters suggested scheduling time to meet prior to a professional exchange; spending the time to get to know the people within the council or community center is important before getting to work. Showing that you are passionate and serious is also important. Carrlee agreed with this noting, the less we talk and more we listen, the better. Overall, both conservators advise clear, respectful communication, removing your ego, and recording stories and words when given permission to do so. In this way, as conservators, we can do our part to help care for these living cultures and their belongings.

Smithsonian Arctic Studies Center “Material Traditions” series:

- Sewing gut: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zEsdWclLlDs

- Sewing salmon: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u38rPWITkjc

- Dene quill art: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CMHgEFkv_4c